A braid was held up as a trophy. Not to win a fight, but to humiliate a woman after death. The camera mattered, because the point was never only the act. The point was the message.

In January 2026, Kurdish and regional outlets reported footage of a man holding up a severed braid and claiming it was taken from a Kurdish female fighter from the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) after her death. Rudaw reported that some sources identified the man, but it could not independently verify that identification. That caution is the correct standard. If we care about women’s dignity, we should also care about truth.

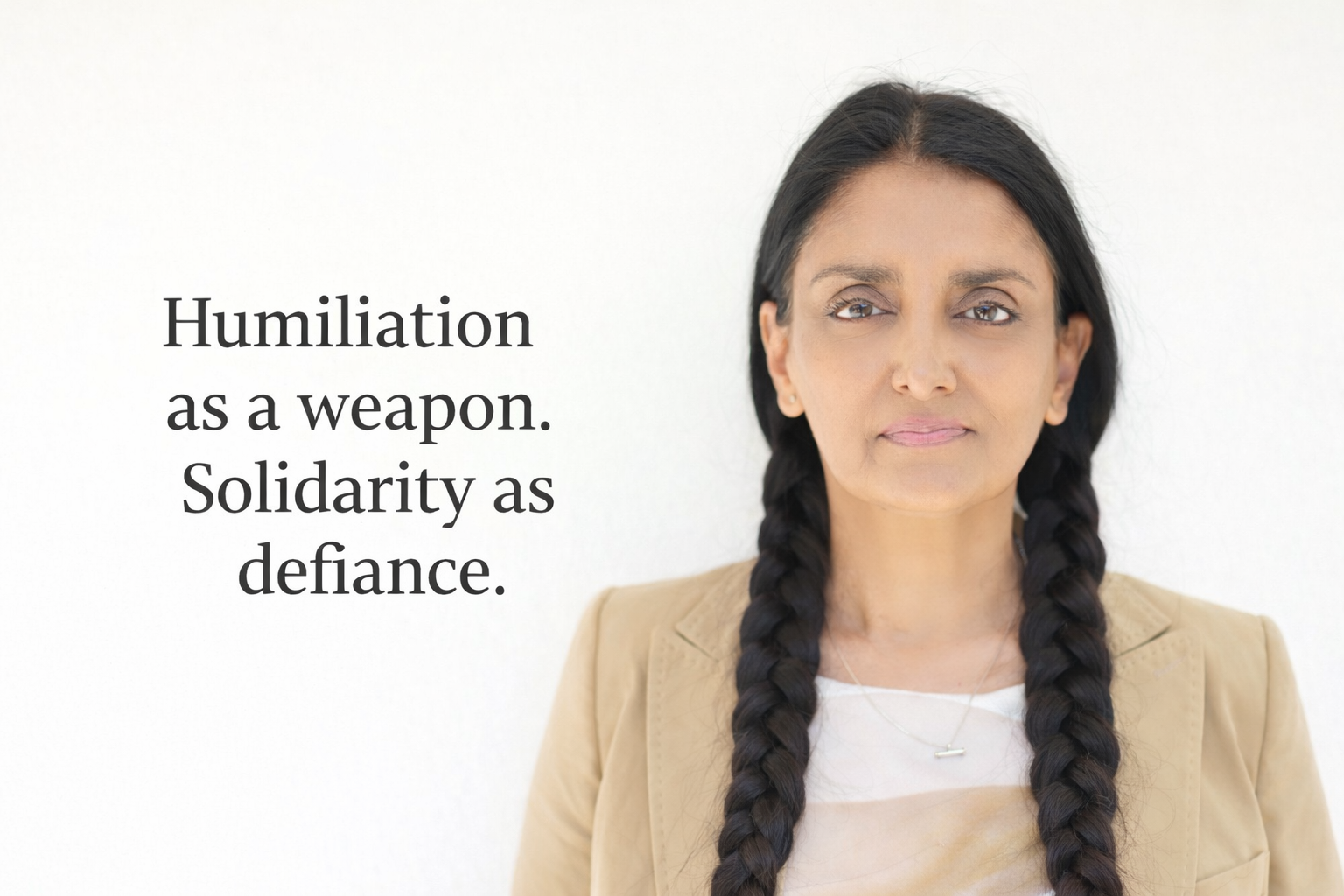

Then came the reply. Women began braiding their hair on camera and sharing it in defiance. bianet described the campaign spreading rapidly, moving from social media into public life. The message was simple: you can cut one braid, but you cannot cut what it stands for.

Strip away rumour and the core facts still hold.

A braid was cut from a dead woman and displayed as a trophy in filmed mockery. That is not incidental cruelty. It is humiliation made performative.

The backlash was equally clear. Kurdish women, and allies beyond Kurdish communities, braided their hair as a public refusal. In parts of north east Syria, protests were also reported where women braided one another’s hair in solidarity.

To outsiders, this can look like a gesture. In Kurdish life, a braid carries meaning.

A museum feature on Kurdish visual culture notes that intricately braided hair is commonly worn with traditional dress, particularly around Newroz, and it records older mourning practices where women cut off braids at gravesites. Braids can hold pride, memory and grief in a single thread.

Rudaw also reports a Kurdish researcher describing the braid as culturally significant, and in recent history a symbol of female power and resistance. That matters, because it explains the intent behind the trophy. If you want to degrade someone, you target what they value, not what is replaceable.

Humiliation is used because it travels.

A killing ends a life. A trophy aims to control the living. It is designed to do three things at once: dehumanise the victim, warn other women, and reward cruelty with status.

The filming is not a side detail. The camera turns degradation into propaganda. It spreads fear without a single extra act of violence.

That is why the Kurdish braid protest landed so powerfully. It interrupted the intended lesson. It refused to carry shame on the victim’s behalf.

In UK safeguarding, so called honour based abuse is not one offence. It is a context where violence, threats, intimidation, coercion, or abuse are used to enforce a code of behaviour and defend perceived “honour”.

The braid trophy sits on the same continuum. The setting is war, but the mechanism is familiar: a woman’s body is used to police other women, and public shaming is used to enforce obedience through fear.

That is why “dishonour abuse” fits. There is no honour in public degradation. There is only power claiming the right to humiliate.

International humanitarian law does not treat humiliation as a footnote.

Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions prohibits “outrages upon personal dignity”, including “humiliating and degrading treatment”.

The International Committee of the Red Cross also sets out how the Rome Statute includes “committing outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment” as a war crime provision.

The legal language is direct for a reason. Dignity is not decoration. In conflict, humiliation is often used to terrorise communities and to erase the humanity of the dead. The ICRC’s International Review has examined this specifically in relation to “outrages against the personal dignity of the dead”.

Solidarity matters. However, it has to be smart, otherwise it amplifies the original harm.

The footage tried to make shame contagious. The response made defiance contagious instead. That is the difference between propaganda and solidarity.

It is a wave of solidarity where women braid their hair in defiance after footage showed a braid cut from a dead Kurdish YPJ fighter and displayed as a trophy.

Because braids can carry identity, tradition and memory. When they are cut by force, it signals an attack on dignity, not just a body.

Because humiliation spreads fear quickly. It turns violence into a message aimed at controlling the living through shame.

Common Article 3 prohibits outrages upon personal dignity, including humiliating and degrading treatment. The Rome Statute also includes related provisions.

Do not share the trophy footage. Share the braid response, explain your reason, and support credible work that protects women and girls.

Aneeta Prem is a UK safeguarding campaigner and founder of Freedom Charity. She provides media comment on forced marriage, FGM, dishonour based abuse, and gendered coercion and control.

Media enquiries: https://www.aneeta.com/contact

Rudaw (22 Jan 2026): Kurdish women braid hair in protest of brutality

https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/22012026

bianet (Jan 2026): Desecration sparks hair braiding campaign

https://bianet.org/english

ICRC: Rome Statute, Article 8 (outrages upon personal dignity)

https://www.icrc.org/en/document/article-8-statute-international-criminal-court

ICRC International Review: War crime of outrages against personal dignity of the dead

https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/the-war-crime-of-outrages-against-the-personal-dignity-of-the-dead-929

Common Article 3 text (ICRC PDF)

https://elearning.icrc.org/detention/en/story_content/external_files/Article%203%20common%20GC%20%281949%29.pdf

CPS: What is ‘honour’-based abuse and harmful practices?

https://www.cps.gov.uk/types-crime/violence-against-women-and-girls/honour-based-abuse/what-honour-based-abuse-and-harmful-practices

CPS legal guidance: Identifying and flagging SCHBA and forced marriage

https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/so-called-honour-based-abuse-and-forced-marriage-guidance-identifying-and-flagging

College of Policing: Honour-based abuse guidance overview

https://www.college.police.uk/guidance/major-investigation-and-public-protection/honour-based-abuse/honour-based-abuse-guidance-overview

Kajal Saini and Mohammad Arman were found dead in Uttar Pradesh, and the language used to describe their murder matters.

A piece of footage showed a Kurdish woman fighter’s braid being displayed as a trophy after her death. The article explains why that act is not “just war”, but deliberate humiliation aimed at policing women through shame. It then explains why braids carry cultural meaning in Kurdish life, why perpetrators stage degradation for propaganda, why this fits the wider pattern you call dishonour abuse, what international law says about humiliating and degrading treatment, and what a responsible response looks like without spreading the original harm.

A school gate does not look like violence until it becomes a judgment repeated for years. UNESCO says Afghanistan is now the only country in the world where secondary and higher education is strictly forbidden to girls and women. UNICEF warns millions of girls are being denied education, with consequences that reach far beyond classrooms.

The Gambia’s Supreme Court is hearing a case that could weaken the ban on FGM. This clear explainer shows why it matters for child protection worldwide.

When families watch, follow and report: the hidden stalking dynamic behind forced marriage and dishonour abuse

How AI nudification is turning everyday photos into a new form of sexual abuse against children Two strong alternatives, depending on outlet tone: How AI nudification apps are normalising sexual abuse and putting children at risk